BARA Bugle (Broadmead Area Residents Association Newsletter),

Spring 2008 – John Lucas

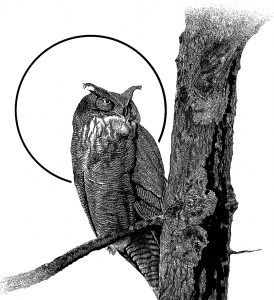

My seventh year was filled with the usual adventures of every boyhood. Among the best of these were the “field trips”, as he called them, with my brother Eugene, recently returned from the war in the Pacific. Depending on our “prey” we set out in the mornings, the afternoons, and in the evenings. One of the most memorable outings occurred on a warm August night lit by a full moon when Eugene decided we should see Bubo virginianus, the Great Horned Owl.

My seventh year was filled with the usual adventures of every boyhood. Among the best of these were the “field trips”, as he called them, with my brother Eugene, recently returned from the war in the Pacific. Depending on our “prey” we set out in the mornings, the afternoons, and in the evenings. One of the most memorable outings occurred on a warm August night lit by a full moon when Eugene decided we should see Bubo virginianus, the Great Horned Owl.

I must confess I greeted this plan with some trepidation: My brother had shown me pictures of this raptor and had described it as a bird that could include in its diet fairly large prey. At age seven I wondered if I fit that description in the eyes of one of the scariest-looking birds in our collection of photographs. When I asked him about this, Eugene replied that it depended on what else was available. In that trusting way little brothers have with their big brothers, I went with him anyway, swallowing my fear and not wanting to look like a wimp.

As we walked Eugene told me that the bird, native to North and South America, was first seen by English settlers in the colony of Virginia and so is named after Elizabeth I, the Virgin Queen. He stretched his arms wide and said that its habitat is enormous, encompassing an area from the Arctic to South America. The Great Horned Owl could be found in all sorts trees: conifers, deciduous trees, and in areas from very dense forests to prairies and deserts. Among owls, it is second in the vastness of its range only to the Barn Owl.

We entered a copse of trees and my brother said I should not talk for a while. All I had to do is listen. Within moments I could hear the various sounds of life around us and then, “Hoo-Hoo—Hoooo—Hoo-Hoo”. Eugene whispered that we were hearing the Great Horned Owl. He scanned the trees with what I now know was a very practiced eye. “There”, he whispered and pointed.

I looked up to where he pointed and there, sitting on a near-bare branch, was the most beautiful bird I had ever seen. Eugene made the slightest “nuck” sound with his tongue and the owl snapped his head toward us. I had never seen such an intense look on any creature and instinctively I moved closer to my brother until I was nearly behind him. He seemed to be staring straight into my soul. He was big and gray with darker bars and wore leggings that looked as soft and downy as silk. A moment later he flew off and my breath was taken away by the enormous sweep of his wingspan.

That was more than sixty years ago and now I live in Broadmead with regular nocturnal visits by Great Horned Owls on the lookout for a meal. Their voices no longer frighten me but instead remind me of Eugene, now long dead, from whom I learned so much about this magnificent creature.

I learned that the female was a bit larger than the male, that the sexes had differing voices and that, depending on the climate of a particular habitat, their colour ranged from pale grey in the Arctic to deeper grays and reds in others. If you listen carefully you can distinguish the calls: the male’s voice is deeper than the female’s and hers rises in pitch at the end of the call, while his dips slightly.

The average size of a Great Horned Owl is about twenty-two inches with a wingspan of about forty-nine inches. Its vision is exceptional. The iris of its eye is yellow and the eye is fixed in a bone socket, incapable of movement such as is the case with our eyes. Instead it is able to swivel its head nearly three-hundred degrees and adults have large tufts of hair at the sides of the head, hence “horned”. Many people think these are ears but they are not and have nothing to do with the owl’s astonishing hearing. Their ears are set at two different levels on their heads so that as their heads swivel they can pick up a greater range of sounds.

We all thrill to the sight of a Great Horned Owl in flight and its quietly effortless gliding and swooping. This raptor has very specialized feathers on the leading edge of its wings: Instead of sharp-edged, “svelte” feathers, it has fluffy ones, to create a silent flight. With no hissing or swishing sound effects, this owl has a tremendous advantage over unsuspecting prey.

The Great Horned Owl has an extensive diet that includes relatively large prey, from rats and rabbits to voles and weasels and even other owls. It is singular among owls in that it regularly eats skunks. It is a superb hunter whose talons have a crushing power of about five hundred pounds.

Our subject mates in December, January and February (depending on location) and usually produces a clutch of two eggs. It will use the nests of other birds adding some of its own feathers as interior decoration. It will also use hollow tree trunks, large squirrel nests, snags, crags, and abandoned buildings.

Luckily for us, the Great Horned Owl is a permanent resident of its territory so we can see it in all seasons. Unluckily for our Broadmead and Rithet’s Bog resident, among its predators is the feral cat, also now permanently resident at the bog and our treed areas.

(This is the third in a series of articles on Broadmead Birds written by John Lucas)